Exclusive: Inside the Supreme Court's negotiations and compromise on Idaho's abortion ban

By Joan Biskupic, CNN Chief Supreme Court Analyst

Updated 8:32 AM EDT, Mon July 29, 2024

No recorded vote was made public, but CNN has learned the split was 6-3, with all six Republican-nominated conservatives backing Idaho, over objections from the three Democratic-appointed liberals. But over the next six months, sources told CNN, a combination of misgivings among key conservatives and rare leverage on the part of liberal justices changed the course of the case. The first twist came soon after oral arguments in late April, when the justices voted in private on the merits of the conflict between Idaho and the Biden administration. There suddenly was no clear majority to support Idaho, sources said. In fact, there was no clear majority for any resolution.

As a result, Chief Justice John Roberts opted against assigning the court’s opinion to anyone, breaking the usual protocol for cases after oral arguments. That move would have marked a startling turn of events for any dispute, but it was particularly surprising here because the court had already given Idaho the advantage by granting its appeal before a hearing on the merits of the case could be held in a US appellate court. Instead, a series of negotiations led to an eventual compromise decision limiting the Idaho law and temporarily forestalling further limits on abortion access from the high court. The final late-June decision would depart from this year’s pattern of conservative dominance.

This exclusive series on the Supreme Court is based on CNN sources inside and outside the court with knowledge of the deliberations.

White House response to overturning Roe

In August 2022, the Justice Department sued Idaho, seeking an order that would block the state from enforcing its ban in emergency rooms when it conflicts with EMTALA. Idaho lost in an initial proceeding in a US district court, as a judge issued a temporary injunction against the abortion ban. While an appeal was pending, Idaho sought the high court’s intervention.

The impact of the justices’ January order allowing Idaho’s ban to take effect was urgent and immediate. The state’s largest provider of emergency services increasingly had to airlift pregnant women experiencing complications out of state. As the weeks passed and Idaho and the federal government began formally making their case in filings before scheduled April oral arguments, the situation for pregnant women in medical emergencies – risking organ failure, the loss of fertility and permanent disability – became more evident. So did defects in some of Idaho’s claims. Its lawyers argued that EMTALA would require hospitals to terminate a pregnancy if a woman’s mental health (rather than physical condition) required it and would force individual doctors to perform abortions despite conscience objections – two contentions US Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar said were groundless. Idaho’s built-in lead began to slip, particularly against the larger national backdrop over agitation for reproductive rights and the politically charged presidential election season. The court had given Idaho the advantage in January by granting its request for an early hearing. Such expedited review is allowed only when, according to Supreme Court procedure, “the case is of such imperative public importance as to justify deviation from normal appellate practice.”

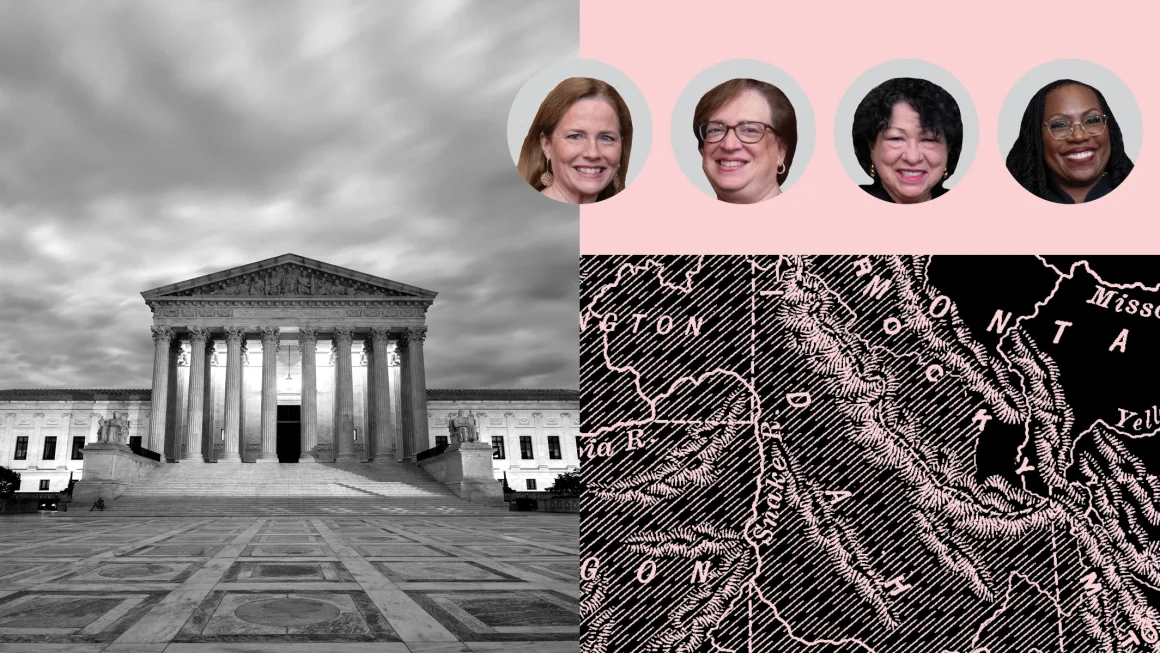

During the April 24 hearing, signs that the conservative bloc was splintering emerged. Justice Amy Coney Barrett, who had earlier voted to let the Idaho ban be enforced, challenged the state lawyer’s assertions regarding the ban’s effect on complications that threatened a woman’s reproductive health. She said she was “shocked” that he hedged on whether certain grave complications could be addressed in an emergency room situation. Barrett’s concerns echoed, to some extent, those of the three liberals, all women, who had pointed up the dilemma for pregnant women and their physicians. Doctors in Idaho had told the court that if they complied with federal emergency-care law and helped a pregnant woman in peril, they would be risking criminal conviction. Alternatively, if they transferred patients needing stabilizing care out of state, they risked seriously delaying medical attention and could exacerbate the harm.

Private vote and rare liberal leverage

She would eventually deem acceptance of the case a “miscalculation” and suggest she had been persuaded by Idaho’s arguments that its emergency rooms would become “federal abortion enclaves governed not by state law, but by physician judgment, as enforced by the United States’s mandate to perform abortions on demand.” She believed that claim was undercut by the US government’s renouncing of abortions for mental health and asserting that doctors who have conscience objections were exempted. In essence, Barrett, along with Roberts and Kavanaugh, were acknowledging they had erred in the original action favoring Idaho, something the court is usually loath to admit. They attributed it to a misunderstanding of the dueling parties’ claims – a misunderstanding not shared by the other six justices, who remained firm about which side should win. During a wide-ranging talk at a legal conference in Sacramento on Thursday, liberal Justice Elena Kagan said the court may have learned “a good lesson” from the Idaho case: “And that may be … for us to sort of say as to some of these emergency petitions, ‘No, too soon, too early. Let the process play out.’” During internal debate from the end of April through June, the court’s three other conservative justices – Samuel Alito, Clarence Thomas and Neil Gorsuch believed the facts on the ground were clear and that Idaho’s position should still prevail. They said the 1986 EMTALA did not require hospitals to perform any abortions and could not displace the state’s ban.