The year is 1981.

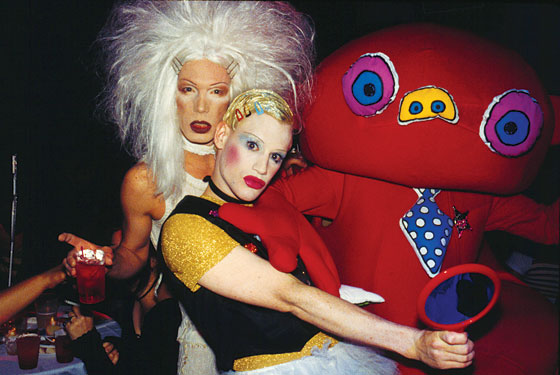

Disco beats pulsate in nightclubs, neon lights paint the streets, and a new wave of optimism washes over the world. It was a time of progress, change, and the promise of a brighter future. But beneath the surface, a silent threat emerges.

A mysterious illness begins to strike, claiming victims with alarming speed. Fear and confusion grip communities, particularly those on the fringes, as a mysterious illness, initially called GRID (Gay Related Immunodeficiency Disease), begins to spread, striking down young, healthy men with alarming speed.

Whispers of a "gay plague" ignited panic, fueled by misinformation and a lack of understanding. Marginalized communities, particularly gay men and people of color, faced the brunt of the crisis, ostracized and blamed for the disease.

With information scarce, misinformation rampant, and the medical community struggling to understand the virus, discrimination, and stigma spread even faster than the disease itself.

Uncertainty hung heavy in the air, and the silence was deafening. Not just in the clubs but in the media, government pronouncements, and hushed conversations behind closed doors. This suffocating silence bred despair and isolation, leaving a desperate need for answers and a community yearning to be seen and heard.

Yet, amidst the despair, a powerful counter-narrative emerged. Artists, musicians, and activists found their voices, using music to challenge the silence, shatter stigma, raise awareness, and demand justice.

Music, that universal language, became a lifeline for a community grappling with loss, fear, and the desperate need to be seen and heard. It offered a platform for expressing their frustration. It became a tool for education, awareness, and, most importantly, a call to action.

From such desperation rose the "Soundtrack of Resistance" — a testament to the enduring power of music in the face of adversity. From disco beats to anthemic rock, from heart-wrenching ballads to empowering dance anthems, each song became a story of courage, defiance, and the unwavering fight for justice and equality.

This is the dawn of the 1980s AIDS crisis in the United States, a defining chapter in human history that forever changed the landscape of healthcare, social justice, and, yes, music.

In the face of government inaction and widespread societal stigma during the 1980's AIDS epidemic, '80s music emerged not only as a beacon of hope but also as a formidable form of protest. Fear and stigma initially silenced many, but musicians and artists soon shattered the silence, courageously using their voices and platforms to draw attention to the crisis, fight for research, and support those facing incredible adversity. Benefit concerts, such as the groundbreaking Live Aid and the passionate Red Hot + Blue project in the early 90s, united musicians of every genre and harnessed the global reach of pop culture. Here, music wasn't merely entertainment; it became a catalyst for both fundraising and a critical shift in awareness. Pop superstars like Elton John, Madonna, George Michael, and the band Queen were among the first to break the silence about AIDS. With their massive global reach, they brought vital awareness to the crisis. Elton John, deeply impacted by the loss of friends–including teenage HIV-positive patient Ryan White – established the Elton John AIDS Foundation, raising millions for care and research. Queen's lead singer, Freddie Mercury, while living with HIV/AIDS himself, performed an unforgettable set at Live Aid in 1985, mere months before his tragic passing. His legacy became a rallying cry for action. Openly LGBTQ+ musicians like Sylvester, Bronski Beat, and others broke ground by bringing their experiences and activism to the forefront of their music. They created safe spaces of expression and defiance in a time of intense isolation. Even outside the mainstream, punk bands, folk singers, and smaller acts found the courage to use their voices and concerts to challenge stigma and fundraise for those impacted.

While star-studded events drew global attention, it was everyday people in grassroots movements like ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power), where music served as the emotional, motivating soundtrack of their vital, organized fight. Protests and defiant marches drew directly on the soundtrack of activism to rally crowds, channel rage and desperation, and transform the streets into platforms. Slogans became chants, repurposed protest classics provided motivation, and songs of both anger and hope were weapons of dissent. In a time when governments ignored a pandemic, this collective cry through music became impossible to ignore.

In the face of government inaction and widespread societal stigma during the 1980's AIDS epidemic, '80s music emerged not only as a beacon of hope but also as a formidable form of protest. Fear and stigma initially silenced many, but musicians and artists soon shattered the silence, courageously using their voices and platforms to draw attention to the crisis, fight for research, and support those facing incredible adversity. Benefit concerts, such as the groundbreaking Live Aid and the passionate Red Hot + Blue project in the early 90s, united musicians of every genre and harnessed the global reach of pop culture. Here, music wasn't merely entertainment; it became a catalyst for both fundraising and a critical shift in awareness. Pop superstars like Elton John, Madonna, George Michael, and the band Queen were among the first to break the silence about AIDS. With their massive global reach, they brought vital awareness to the crisis. Elton John, deeply impacted by the loss of friends–including teenage HIV-positive patient Ryan White – established the Elton John AIDS Foundation, raising millions for care and research. Queen's lead singer, Freddie Mercury, while living with HIV/AIDS himself, performed an unforgettable set at Live Aid in 1985, mere months before his tragic passing. His legacy became a rallying cry for action. Openly LGBTQ+ musicians like Sylvester, Bronski Beat, and others broke ground by bringing their experiences and activism to the forefront of their music. They created safe spaces of expression and defiance in a time of intense isolation. Even outside the mainstream, punk bands, folk singers, and smaller acts found the courage to use their voices and concerts to challenge stigma and fundraise for those impacted.

While star-studded events drew global attention, it was everyday people in grassroots movements like ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power), where music served as the emotional, motivating soundtrack of their vital, organized fight. Protests and defiant marches drew directly on the soundtrack of activism to rally crowds, channel rage and desperation, and transform the streets into platforms. Slogans became chants, repurposed protest classics provided motivation, and songs of both anger and hope were weapons of dissent. In a time when governments ignored a pandemic, this collective cry through music became impossible to ignore.

Crack hit the streets around the time of what Abe calls, “The Golden Era of Hip Hop”, which was happening in the mid-80s and mid-90s. That’s when hip hop starting hitting the mainstream and there was a variety of hip hop artists making their mark.

But the 1980s was also a time when the US was going through a recession. Abe says a lot of people were out of a job and more and more people were being denied opportunities and that impacted families.“You start to have families that are breaking up traditional family structure. Young people kind of searching for alternatives to family and that eventually kind of morphs into what we see today as the street gangs,”Abe says.

And Abe says the crack epidemic didn’t help. “So this kind of drug epidemic was something that was different because the high was such a rush and so intense but it would only last a few minutes so people would keep coming back for more. It was almost like the fast food of drugs. And as there’s money to be made, people are starting to figure out ways in which to make it. This is something that happened in Seattle, where dealers would rent out houses and stick an immigrant family in the house to run the sales and people would literally be lining up around the corner to go up to this crack house and do what they needed to do. So it was literally like people going through the drive through to get their drugs."

Abe continues,The amount of money that it turned over, first of all, it attracted a lot of people into it and it also encouraged competition, not healthy competition for the most popular spots and with that amount of money you’re able to buy firepower. If you’re feeling like your competition has a pistol, you might go get a rifle. So it was unlike anything that you had seen before. People lined up around the corner. It was people going through drive through to get drugs. It attracted a lot of people. You’re able to buy firepower. You might get a rifle. So it was unlike anything you’d seen before, especially as gangs become involved in it. Gangs became a natural distribution network. Once they get into distributing crack things really kind of spiraled out of control in terms of gang violence."

Abe says you started to hear about the crack epidemic in hip hop music.

“Hip hop has always been about telling who you are and where it’s like where you’re from so more and more it became people were from these areas that were negatively impacted, not only by crack but also the aftermath and what it was doing to people and what it was doing to families and how people were going to jail and how people were dying and getting arrested people and it starts to show up in the music.

Abe points to the songs, 10 Crack Commandments by The Notorious BIG where he lists the rules to selling crack.

“What he’s doing is really telling a story in terms of how horrific the whole thing was,” Abe says.

There was the song, Dopeman by NWA that helped define some of the terminology being used around crack—such as “strawberry”, someone who trades sexual favors for crack. Abe also says the song, "My Summer Vacation" by Ice Cube discusses the hows and the whys of the crack epidemic.

“That song really does, in my opinion, a great job of setting the stage of how gangs and crack really moved around the country from Los Angeles. . . Ice Cube . . . detail[s] how him and his crack selling friends go to St. Louis where if you buy a kilo of cocaine in Los Angeles for $6,000, you can flip it and sell it in St. Louis for $18,000-$19,000. You see the lure of money. You can see the competition that can be created when there’s a denial and lack of opportunity in a community that is at the same time supplemented by underground economic opportunities that not only pay well but probably pay better than any job you would be able to find if you were able to find a job,” Abe says.

Finally, Abe discussed Public Enemy’s song, "Night of the Living Baseheads." He says the song and video takes a stance that criticizes “white folks” but also “black folks for using it.”