Promoting human rights for Taiwan’s fishermen: Collaboration with the primary source countries of Taiwan’s DWF migrant fishermen

Po-Chih Hung, Hsiao-Chien Lee, Chih-Cheng Lin, Wen-Hong Liu

Taiwan is one of the largest distant water fishing (DWF) nations worldwide, and relies largely on the migrant labor to keep costs low. However, this industry has caused Taiwan to be listed in the 2020 “List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor” of the U.S. Department of Labor. In view of this, the Taiwanese government is actively adopting further management measures to supervise the domestic and foreign fishermen agencies. It is because the latter has been involved in many disputes, especially in recruitment, payroll, and labor contracts, which directly or indirectly affect the rights of migrant fishermen. On the other hand, although the C188 Work in Fishing Convention has stregthend the protection of the fishermen’s human rights, it still stays ambiguous in terms of private agency management. That is also why so many disputes have been caused in recent years.This study conducts a comparative analysis of the agency management systems in the primary source countries of Taiwan’s distant water fishing migrant fishermen (that is, Indonesia, the Philippines, and Vietnam), as well as interviews with distant water fishing stakeholders to provide insights on the improvement of agency management and migrant fishermen’s rights in Taiwan. The findings imply that the positive interaction, mutual trust, and understanding of laws and regulations between fishermen’s exporting and importing countries lead to future cross-national collaboration. This study suggests that the Taiwanese government should follow the spirit of the C188 but not be restricted to the Convention texts to amend or formulate regulations and policies of agencies for fully protecting the rights of migrant fishermen.

Introduction

More than 40 million people worldwide are trapped in modern slavery, and more than 24 million are in forced labor (Minderoo Foundation, 2018). The global fishing industry is currently plagued by forced labor, and consumers are unaware of the true cost of buying seafood in shops or restaurants, while exploited workers are exposed to the risk of unpaid labor, exhaustion, violence, injury, and even death. Therefore, the distant water fishery industry is considered one of the most dangerous occupations. The majority of this workforce comes from Southeast Asia, where unethical agencies target vulnerable groups such as the poor, and recruit fishermen in large numbers without the commitment to good wages at sea (The ASEAN Post, 2019; Scalabrini Migration Center, 2020; Urbina, 2022), violating United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 10: Reduce inequalities.

In 2020, the U.S. Department of Labor (USDOL) reported the 2020 List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor. For the first time, Taiwan’s DWF products were listed as forced labor and included in the list, seriously affecting Taiwan’s international reputation (Thomas, 2020). According to the report, although Taiwan’s DWF industry is ranked second only to China, migrant fishermen often encounter forced labor issues, such as unpaid wages, withholding of passports, excessively long working hours, hunger, and dehydration; these are severe violations of forced labor rules. The report points out that during the recruitment process, overseas agencies sometimes use false wages or contracts to deceive fishermen and require them to pay recruitment fees and sign debt contracts (USDOL, 2020).

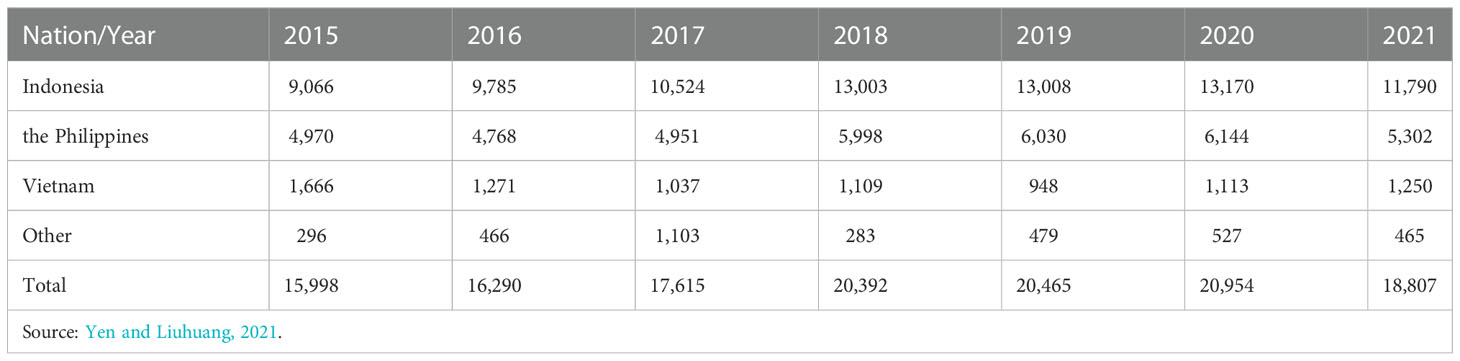

Fishing is a labor-intensive industry, and labor shortages have appeared acute in Taiwan due to the industry structure change. Therefore, importing foreign crew has been the primary means of filling the labor gap. The statistics exhibit that the number of domestic DWF workers in Taiwan has dropped from 26,000 in 1990 to 12,000 in 2020, and it is still showing a trend of continuous decline. Moreover, in 2021, Taiwan’s DWF enterprises employed 18,807 foreign workers, of which 11,790 (62.7%) from Indonesia, 5,302 (28.2%) from the Philippines, and 1,250 (6.65%) from Vietnam are the top three exporting countries for migrant fishermen in Taiwan, far exceeding the number of domestic workers of distant water fishermen. The number of fishermen from these three countries exceeds 90% of the foreign workers (Scalabrini Migration Center, 2020; Aspinwall, 2021; Yen and Liuhuang, 2021) (Table 1).

Challenges for fishermen-exporting countries in migrant labor management

“Philippines Overseas Employment Administration”(POEA)was established in 1974 under the Labor Code of the Philippines. The original name was Overseas Employment Development Board(OEDB), then changed to its current name in 1982. The mission of POEA is to manage the export of migrant workers overseas and to protect the rights and interests of migrant workers. There are two central legal/regulatory systems for private agencies in the Philippines: “1995 Migrant Workers and Overseas Filipinos Act” and “Labor Code of the Philippines” (POEA, Philippines, 1995; DOLE, Philippines, 2017). The rules related to the overseas placement of fishermen include “Rules and Regulations Governing the Recruitment and Employment of Seafarers”, “Standard Terms and Conditions Governing the Overseas Employment of Filipino Seafarers Onboard Ocean-going Ships”, “2016 Revised POEA Rules and Regulations Governing the Recruitment and Employment of Seafarers” (POEA, Philippines, 2003; POEA, Philippines, 2010; POEA, Philippines, 2016).

However, in recent years, agencies have often exploited Filipino fishermen overseas in terms of wages, including excessive monthly payroll deductions and placement fees or job search fees to disguise high loans. This situation exists not only in Philippine agencies but also in Taiwan (Taiwan News, 2020). In fact, Filipino and Taiwanese agencies have charged various fees to Filipino fish workers, including transportation, documentation, training, and medical fees. This situation also makes it necessary for Filipino fishermen to pay certain types of fees to obtain a job, and these practices have long been in the gray area of the laws, or even illegal in the Philippines and Taiwan (Verité, 2021). Moreover, illegal agencies in the Philippines often recruit fish workers in the countryside, using deceptive and unrealistic wages, and refund of deposits to lure in cooperative Taiwanese fishing vessels. (personnel of Rerum Novarum Center, personal communication, 2021/09/02; Urbina, 2015). Therefore, the migrant worker agency is the problem that needs to be addressed urgently for the Philippine government.

Given that the economy is opening up and the number of migrant workers is increasing rapidly, the Department of Labor and Employment(DOLE)of the Philippines asserts that the government should ensure fair and ethical recruitment as the key to helping Filipinos choose to work overseas. The Philippines has been actively adopting immigration policies and frameworks for a long time. In order to further protect the rights and welfare of Filipino migrant workers, “National Action Plan to Mainstream Fair and Ethical Recruitment”(NAP-FER) plays an important role. NAP-FER is a significant commitment of the Philippines fully engaged to promote the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly, and Regular Migration (GCM) and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) with six strategic goals: 1. formulate a reward system and strengthen the existing overseas labor recruitment registration and approval system;2. develop a code of ethical standards for overseas labor recruitment and encourage its adoption by private recruitment agencies and staffing industry associations; 3. develop and promote due diligence and self-assessment tools to enhance and simplify current policies and systems based on international fair and ethical recruitment standards;4. ongoing capacity building in fair and ethical recruitment principles and standards; 5. launch extensive informational, educational, and communicational campaigns to raise awareness of legal employment processes, illegal employment and human trafficking risks, and worker rights and responsibilities; 6. Improve existing reporting, monitoring, and remediation of Filipino migrant workers to address gaps in grievances, perceptions, and descriptions of previous mechanisms (DOLE, 2021; Leon, 2021; Noriega, 2021). From the above, it is clear that the role of Philippine agencies is highlighted during migrant worker recruitment by the government, and the international ethical standards are gradually adopted for future recruitment and incorporated into the National Action Plan to protect Filipino migrant workers overseas.

The NAP-FER follows the guideline: “Robust Legal and Policy Framework That the Philippines Already Has As One of the Top Labor-Sending or Worker-Deploying Countries Worldwide”, which has five key elements: 1. facilitate fair and ethical employment and ensure decent working conditions; 2. promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment, and decent work for all; 3. reduce inequalities within and between countries; 4. protecting the rights, promoting the welfare, and increasing the opportunities of overseas Filipinos (OFs) in “Philippine Development Plan 2017-2022”; 5. National and international legal and policy frameworks such as Committee on Migrant Workers (CMW), International Labor Organization Conventions (ILO Conventions), relevant Philippine laws, and POEA regulations (Baclig, 2021).

Conclusion

Inorder to promote human right of DWF migrant fishermen in Taiwan, it is necessary to understand the agencies management. The agencies always play the key role to connect importing and exporting countries of DWF migrant fishermen. And people find agencies might be the one of main causes to infringing upon human rights of DWF migrant fishermen. However, ILO C188 is still not to deal with agencies management yet. In the light of this, we decide to be based on the agencies management in importing country (Taiwan) to discuss and compare the agencies’ management system、main functions and recruitment system of exporting countries (Indonesia, the phillipines, and Vietnam).

The results showed that the differences in the policies of exporting fishermen or laborers among countries mainly include the management of the agencies, the training mechanism of the recruitment process, and the functions of the agencies. Although every country has made great efforts in protecting its people’s rights when the latter are working overseas, and also are devoted to following the C188, in reality, it is observed that every country holds a particular expectation of the special role that the agencies should play. For instance, the Indonesian government stresses particularly the agency’s role of transferring salaries back to their remote hometown. The Philippine government actively makes international links, and by asking the agencies to understand related regulations, the government helps to reduce disputes and in the meantime encourages the agencies to look for overseas job opportunities so that the country’s labor export policy can be followed. The Vietnamese government expects nationals to return home with the skills and capital after working overseas, in order to to promote local economic development; therefore, the government manages overseas income and realizes the differences in legal regulations between countries to reduce unnecessary disputes.

For fishermen-importing countries like Taiwan, the spirit of the C188 Convention should be followed, but not restricted to the Convention texts, and the laws and policies should be amended or formulated with the goal of promoting international human rights protection. The feasible practices include proactively establishing an agency management mechanism and collaboration platform with fishermen-exporting countries, and indirectly improving the agency’s protection of fishermen’s rights from the employers’ side. In conclusion, Taiwan as a major DWF country, should actively seize opportunities to lead the protection of fishermen’s human rights in the world, thereby implementing global obligations to achieve SDGs.