Introduction

This is my thesis, the culmination of many years of undergraduate study in all things concerning cities. From an initial spark with architectural history of cities, to a current love of education policy, I have studied a wonderfully wide range of topics and found comfort in urban studies. I have been more inspired than ever to create a piece of writing that argues a unique perspective on an important policy topic. I have found a subject I truly care about, that feels deeply personal, and plays on my desire to live in a fairer world, but is conscious of the needs of all people.

The gifted and talented program of my day gave me an escape from a failing system, not because teachers favored me, but because they truly believed in my abilities and needs for accelerated and advanced schoolwork. I believe that there are children out there, of all races and classes, all across our city, who need an advanced curriculum to succeed at their potential, but that it is not a privilege or an elite status to be earned solely through testing, it is a real necessity for these students. I believe that by defining “gifted” students as an elite group we do a disservice to students in genuine need.

A New Look at Gifted and Talented Education: A Study of Segregation and Giftedness in New York City Public Schools

The gifted and talented (G&T) program in New York City public schools is meant to educate gifted children in specialized classes to best serve their needs. Unfortunately, due to a decade old policy change, the G&T program now primarily serves white, Asian and affluent students in public schools, rather than a diverse group of gifted children. Where the program was once directed and implemented by individual school districts, mayoral control has centralized the implementation of most public school programs across the city. That policy change, which led to the creation of a standardized admissions process in which children as young as four years old must test for seats, was intended to create greater racial and economic equity in the education of gifted children. Instead, the G&T admissions process has only added to the distinct and visible racial and economic segregation in the public school system.

In this thesis I will introduce some key concepts critical to thinking about gifted education in New York City public schools. I will provide background on the G&T program for those unfamiliar with it, and describe the two iterations of the program in schools. I will then go into an analysis of segregation in schools caused by the program in its current state. This analysis touches more than just race, however, as I believe this is an understated issue in the media around the program, and encompasses issues of geography, race, income and special populations and student performance which merit study. Then I will discuss integration, the movement towards greater equality in schools and how that has led me to a new look at gifted education through a reframing of the definition of giftedness in public schools. I will discuss this reframed definition and evidence for it from research on giftedness in children and the need for schools to provide specialized services for them. I conclude with take away points from this research and what I hope readers will understand about gifted education.

When I was in the second grade at my neighborhood elementary school, my mother distinctly remembers that I sat at a small round table in the corner of the room with a couple of other students who were too advanced for the class, quietly reading on our own. She had been welcomed by my teacher to sit in for the day and she finally understood why I hated going to school everyday, when I had loved school for years: I was not learning anything. While the teacher was trying to teach most students the alphabet, I devoured chapter books, I knew multiplication and division, I could write small paragraphs. Anything I actually learned that year was because my parents took the time to teach me at night, these were not things I learned in the classroom. The vice principal eventually told them that their best option was to switch my school, that there was a special program in some schools for kids who needed an accelerated curriculum. He gave them an application, and they went to a meeting at the school to turn in a portfolio of all my accomplishments: my nearly perfect report cards, my school projects, my many certificates for literacy, good behavior, student of the month. I got into the program but I did not interview with anyone, I did not take an admissions test, and my parents never had to visit the school more than once, my abilities and accomplishments spoke for themselves.

In the third grade, I went to a new school about six miles away from my home. I was placed in the talented and gifted, TAG, class. That year I felt like a sponge, soaking in everything my new teacher had to offer, from writing my first three-paragraph essays to world history and Earth science. I made great friends in my class who understood me, who I could talk to and who were also hungry to learn. My teacher knew how to pace our class, so no one was ever bored and we were constantly challenged. The long trips to school felt worth it and I was a much happier kid again. My mother still thinks it was one of the best years I had in school, and she was just grateful that I was in a class where I was learning again.

This was in the 1990s, when gifted and talented programs and schools themselves were controlled by individual school districts, so students were identified for gifted classes at the discretion of teachers, administrators and district leaders. The current G&T program administered by the New York City Department of Education (DOE) began in 2006, and in order to understand the breadth of issues the program has been charged with, we need to understand what the program looks like.

Background

The New York City public school system is a massive and complex network of 32 districts and thousands of schools governed by the DOE. Before launching into a discussion of the issues with the G&T program, it is essential to get a grasp of what the program is intended to look like. In this section, I will explain the very basics needed to understand the gifted and talented program in New York City public schools. I will explain the different iterations of the program and how those are implemented in schools, and end with a brief explanation of the application process.

What is G&T?

Gifted and Talented (G&T) is a program in the New York City public school system meant to “support the educational needs of exceptional students”. (G&T DOE site) The G&T program has a standardized admissions process, but how curriculum and services are implemented varies from school to school.

Different Kinds of Schools

One iteration of the program are the Citywide G&T schools. These are five schools where admissions is entirely dependent on the admissions test and all students are classified as gifted, and which have a total of approximately 300 Kindergarten seats available. Three of the schools are in Manhattan, one is in Brooklyn and one is in Queens. Staten Island and the Bronx, the other two boroughs in New York City do not have one of these special schools. In order to be admitted to these schools, students have to score in the 97th percentile, but often times the schools only have room for those in the 99th percentile and still have to use a lottery because of high demand for the limited seats. These schools are unzoned, so students from all parts of the city are welcome to test for seats.

Another iteration is the District G&T, a program in regular district elementary schools, where students are placed together in gifted classes in the major subject areas but may take classes with general education students for physical education, art, etc. These programs may have admissions priority for students who live in the district or zone. In order to be eligible for a seat in the program, applicants must score in the 90th percentile at minimum.

The Application Process

The application process for G&T is separate from Kindergarten enrollment but runs concurrently for most applicants since Kindergarten is generally the entry point for students. This means that at 4 years old, children sit for the admissions test, which contains nonverbal test items from the Naglieri Nonverbal Ability Test (NNAT) and verbal test items from the Otis-Lennon School Ability Test (OLSAT). Of over 14,000 children who sat for the Kindergarten admissions test last year, only 2,305 received offers to a G&T seat.

Segregation

The G&T program has become a frequent target in the greater debate around segregation in the NYC public school system. The program has been identified as an early source of segregation in schools because of its admissions process, which favors white and Asian students of more affluent backgrounds, and children whose parents have the means to prepare them for the test through test prep. The test is the only way to enter the program, and because the seats are in such high demand, it gets harder to get a seat as a child gets older. There are far fewer seats available in the higher grades, keeping the program racially segregated through elementary school. While most parties agree that the admissions process is problematic and needs to be addressed, some integration advocacy groups see the elimination of the entire program as the best way to address the segregation it creates.

In fact, the issue of segregation in the G&T program is actually understated by the news and media that have reported on the problem. The repetition of the diversity statistic, that G&T programs are not representative of the racial makeup of the public school systems, where black and Hispanic children are less than 30% of the population in G&T but over 70% of the population in city schools, does not adequately explain the severity of the segregation in the program. Segregation in the G&T program spans issues of geography, race, income, students with differentiated abilities and academic performance. These disparities have become a symptom of greater segregation in the New York City public school system.

Admissions

Let’s return to the admissions process and its many steps to understand how the segregation begins before students are even placed in the program. Parental involvement at this stage is incredibly important, and the beginning of the difference between what families get into the program, and which ones can’t get to the starting line. A lengthy admissions process and an uneven playing field await families interested in G&T.

A Long Process

At 4 years old, if a child is in Pre-K or not, they will have to go through general Kindergarten admissions in order to be placed in a Kindergarten classroom. This process requires parents to fill out an application form, select 12 Kindergarten programs they would like to attend and rank them. All children are guaranteed a seat in a school, but because some schools are more popular than others, and some are zoned programs (only open to children with specific addresses within the school “zone”), some students will be placed wherever there is room. Parents can fill out the application online, over the phone, or submit in person. Once parents receive an offer, they must bring their child to the school to pre-register/accept the offer.

That all seems very easy, and how long or strenuous the process is depends on the family: families can choose to tour or visit schools in other parts of the city and some schools that are high performing are popular and offer open houses. The process only has two steps that require a parent take action: the application and the pre-registration/offer acceptance.

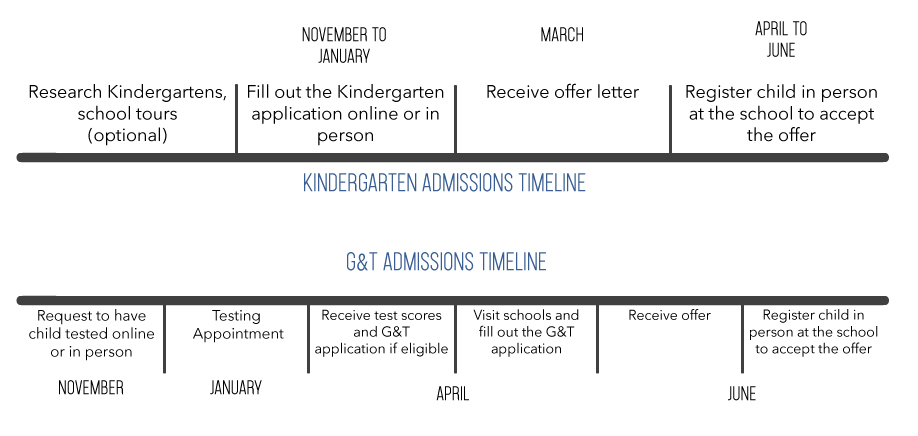

Source: NYC Department of Education

The admissions process for G&T requires many more steps. Firstly, parents must submit an application for testing, which is known as expression of interest in the program. They then need to take their child in on a weekend when they are scheduled for the test, and there are only six days available in January to accommodate all testing families. Tests are administered all over the city, and four year olds are on their own with a tester they have never met before. When parents receive scores in the spring, they must submit another application specifically for G&T schools. The DOE heavily advises it, even lists it on the G&T admissions timeline, unlike for Kindergarten, that parents visit G&T schools, whether they qualify for a Citywide program or District program because:

- Citywide programs are extremely popular and while interest at an open house will not affect the lottery for seats, it is important parents understand how far they will be potentially traveling with their child.

- Not all districts have G&T classrooms, so if a child is eligible for a seat they may still have to go to another neighborhood the family is not familiar with. It is also possible that the family lives in a district with multiple programs, in which case they should see which ones they are most interested in.

Depending on the number of schools they are applying to, this could include many more appointments for open houses and tours. Then, if the child receives an offer to a G&T program, they must go to the school to accept the offer. In addition, all families must go through the regular Kindergarten process, since there is no guarantee, no matter what score the student receives on the tests, that they will be offered a seat. There are also admissions priorities for G&T (children with siblings already in the school, children living in the district, etc.) standing in the way for most seats, in addition to the thousands of applicants who are also eligible vying for the same seats. Parents have to be strategic and research the schools they want to apply for.

Parents have to have a lot of time to go through the G&T admissions process, because they also have to simultaneously complete the Kindergarten admissions process. Parents have to fill out an application just to express interest in the program, not to mention test day, filling out a second application, and going on tours, which creates a barrier for parents with limited time and resources to go through all the steps. Lower income parents are unlikely to have the same kind of time to do the research necessary, any test prep, and to visit the schools even if they do manage to have their children tested. This also does not even tough parents with limited English who may be provided translated resources, but are not necessarily aware of the program for lack of cultural understanding.

Research on parent perspectives of the gifted and talented program shows that there is also racial discrepancy in how parents value going through the admissions process. Researcher and professor of education Allison Roda found in a qualitative study of a G&T district school that white parents were more likely to place high value on testing for the gifted program, and were in social networks that pressured them to do so, and even believed it to be a sign of “good” parenting to test prep for the program. They were also more likely to retest their children in older grades if they did not receive an offer for Kindergarten. Hispanic and black parents with children in the same school’s general education program, however, felt that there was no advantage to testing for the gifted program and that enrolling their children in classrooms where they were going to be in the extreme minority was a sign of poor parenting. (Roda, 2017)

Field Notes: The Bell Curve

At a district G&T school in District 20, which is a higher income, largely white and Asian district in Brooklyn that is also home to six district G&T schools and a citywide G&T school, parents are told not worry about not getting a seat in the gifted class. Classes in this very popular neighborhood school are all differentiated by ability, meaning students are taught at their level no matter what class they are in. So a student in a regular classroom who is learning at an accelerated pace will also received accelerated classwork, just like a student in the gifted class. Teachers track student progress so as to provide them with the most appropriate but challenging classwork and projects. An administrator at this school told me that they tell worried prospective G&T parents that all classes are taught on a “bell curve”, including the gifted classes, so their child will receive accelerated classwork if they require it. This school, even with a set of gifted classes, works hard to identify students who need special attention to learn above grade level. However, only children who live in the zone ever get seats in this popular, high performing school.

An Unfair Advantage

While the long process for applying to the G&T program is just one factor contributing to the segregation in the program, another issue is that affluent parents have been using private tutors and test prep centers to prepare their children for the admissions test. Even if a low income parent had the time to go through the much longer application process, and could have their child tested, chances are they are headed into an uneven playing field. Parents pay thousands of dollars for classes and private lessons (up to $400 per session) at test prep centers to prepare their children for the test because even a few percentage points could make all the difference to be eligible for a seat. (Wall Street Journal) At the very least, the test prep would familiarize a four year old with testing conditions, teach them to sit still and follow instructions, as most children that young have not gone through testing before. The DOE would like to discourage parents from test prep, but they provide sample tests in the G&T admissions guides. Prepping at a center rather than at home is also preferable because it will introduce the child to speaking with strangers, which is most similar to the test day. Test prepping with mommy and daddy at home is not the same as going to a school like setting and working with a teacher who can better simulate the day. Regardless of how parents test prep or how much they pay, this unfairly disadvantages low-income families who do not have the money or time to test prep their children.

Geography

If the lengthy admissions process and unfair advantages in test prep and admissions priorities are not discouraging enough, let’s look at where children would be going to school. As previously mentioned, families need to visit G&T programs to feel out the school environment and distance from home, but what about once the child is admitted? There are places in the city where there are no G&T programs available, and for some families the distance is incredibly far, especially for those in one of the five citywide G&T. The geographic disparities in G&T distribution, where families live, the distance from a school and the school district they live in contributes to the segregation in the gifted program.

Not So “Citywide”

The orange circles on the map above show where the citywide programs are, all five of them. There are three in Manhattan, one in Queens and one in Brooklyn. NEST+m is a K-12 school in the Lower East Side of Manhattan, and once students are admitted they can stay in the high performing school through high school, although the school sends many students to the specialized high schools, and only about a third remain through high school. TAG Young Scholars in East Harlem is just north of the 96th street border with the Upper East Side. The Anderson School is on the Upper West Side, just a block from the Museum of Natural History and Central Park. In Queens, The 30th Avenue School is located in Astoria, a diverse but heavily gentrifying neighborhood. Finally, the Brooklyn School of Inquiry is in residential Bensonhurst.

There are no citywide G&T schools in either the Bronx or Staten Island, and parts of Queens and Brooklyn are so far from the schools available in the borough that it does not make much sense to send a Kindergartener on a bus that far everyday, if a bus is indeed available. The DOE does not guarantee yellow school buses, but students will receive a Metrocard if they are traveling far away.

Field Notes: The Bulletin Board

At one of the citywide G&T schools in Manhattan, a third grade bulletin board displayed letters students wrote introducing themselves to their new teacher. I was drawn in by the length and sophistication of some of the writing at first and cute descriptions of younger siblings until I realized how far away some of these students lived. Bayside and Kew Gardens in Queens, Carroll Gardens in Brooklyn were just some of the neighborhoods the third graders wrote about in their introductions. Most if not all of these students had been going to the school since Kindergarten. When I asked how children who lived so far away got to school, an administrator said that although some students wake up at 5 am to get to school on time, that most parents could afford private buses to make the long trip everyday. Astounded by the idea of kindergarteners waking up at 5am, I turned back to the bulletin board. One student described their home in Brooklyn as “cozy like any home” with three private decks and a rooftop terrace.

District Disparities

While there are many more District G&T programs, 83 across the five boroughs, there are districts that do not have any, or only one, and other districts that have up to six schools with some gifted classrooms.

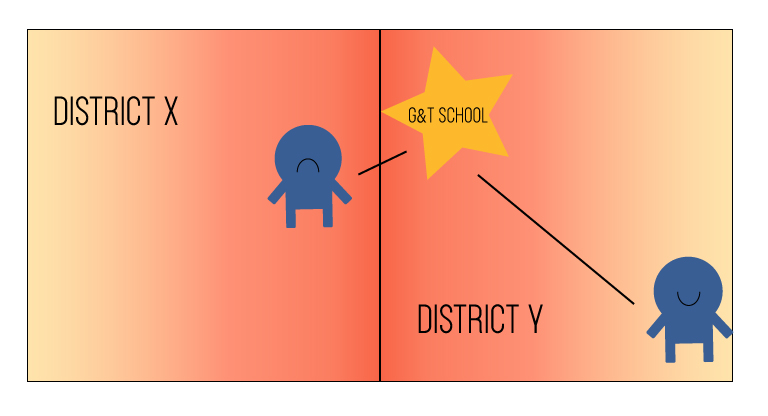

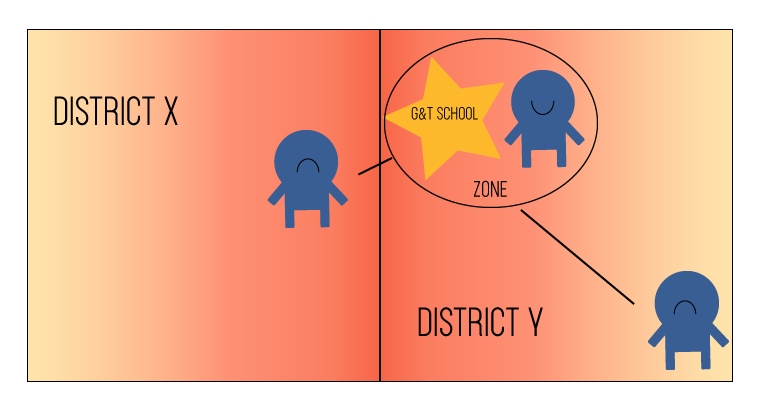

Students who live in a district without a G&T program are at a great disadvantage when applying to District G&T programs because of admissions priorities for students who live within the district. This means that if a student lives in District X, which has no G&T school, but is applying to a school in District Y, all students applying for the same school who live in District Y will be considered before the student living in District X. This is regardless of distance from the actual school. Some students who live on the border of a district with G&T programs may not be eligible for them.

The distance issue remains, even if a student lives in a district that does have a program. Some large districts like District 29, which is in eastern Queens with extremely limited public transportation, have one only district G&T program. Students from many different neighborhoods would have to travel a far distance to get to that one school. For example, students who live in the neighborhood of Rosedale need to be driven 5 miles to the closest G&T program in Cambria Heights, or take three buses and walk 10 minutes.

To further complicate matters, even if a student lives in a district with many, many G&T programs, and they do not receive a G&T offer to a school of their choice, they may not get a seat in a desirable school if they do not live in the school “zone”. Elementary schools are often zoned, meaning they have to provide seats for students who live in the immediate area before they can admit students who live in other areas within the district. So if a student who does not get a G&T offer to a school lives in the school zone, they will likely still be able to enroll in a general education class at that school. As will be discussed, district G&T schools outperform traditional public schools, so even their general education seats are popular.

All this means that even if a student has the qualifying test scores to be eligible for a seat in a gifted classroom, where they live greatly affects whether they get a seat. It will not only depend on which school district they live in, but what zone they reside in. Students who live in a district G&T school’s zone have a chance at a seat in the school, even if they do not receive a G&T offer, over children who live outside the zone. Then there is the trouble that even if they should get a coveted seat in a citywide G&T school, they will likely travel a long distance to get to school. How many parents have the heart to send their kindergartener across the city to get to school, or the time to take them? How many of them can afford a private bus to make the trip?

Race

If the admissions obstacles and geographic inequality were not enough, G&T schools are also incredibly segregated by race. News outlets and media often report the same statistic over and over, that “while 60-70% of the school system is black/Hispanic, black and Hispanic children only make up 30% of students in G&T,” the imbalance is not quite that simple, and deserves further study to understand how different schools in the public school system really are.

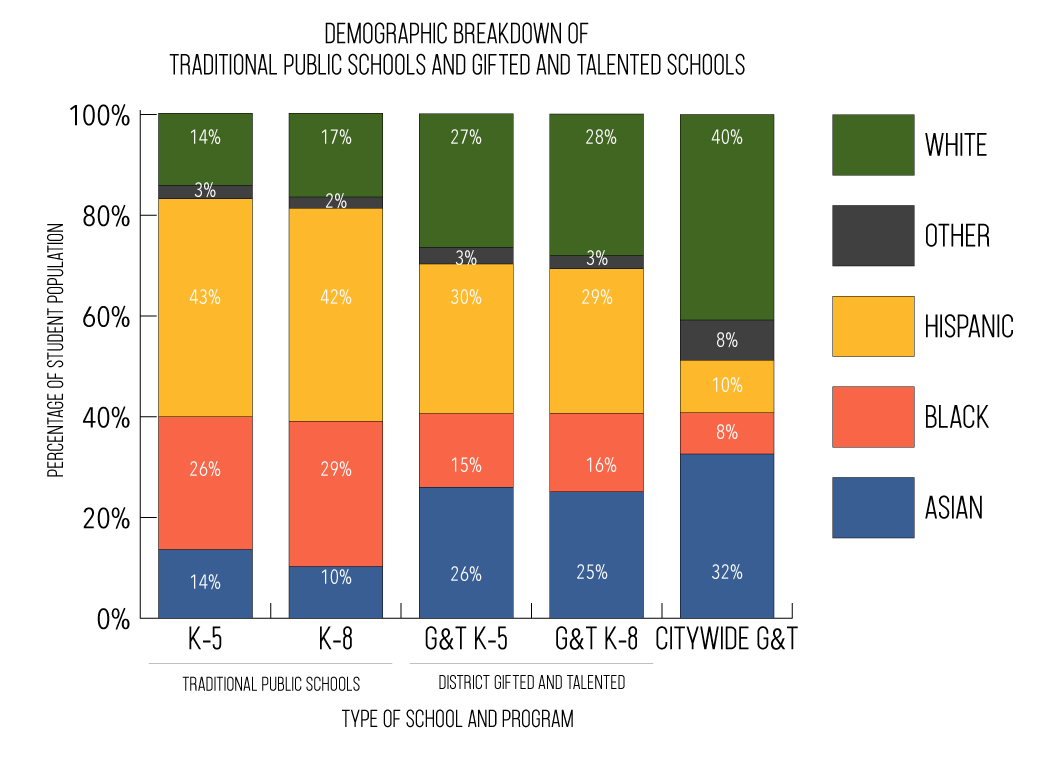

Unpacking the Statistic

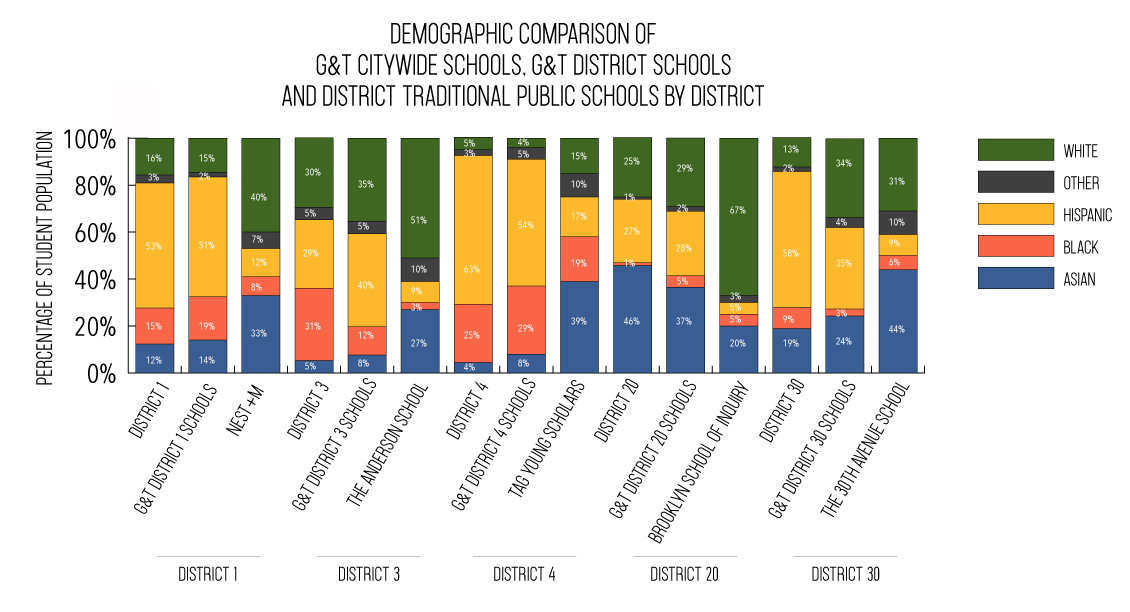

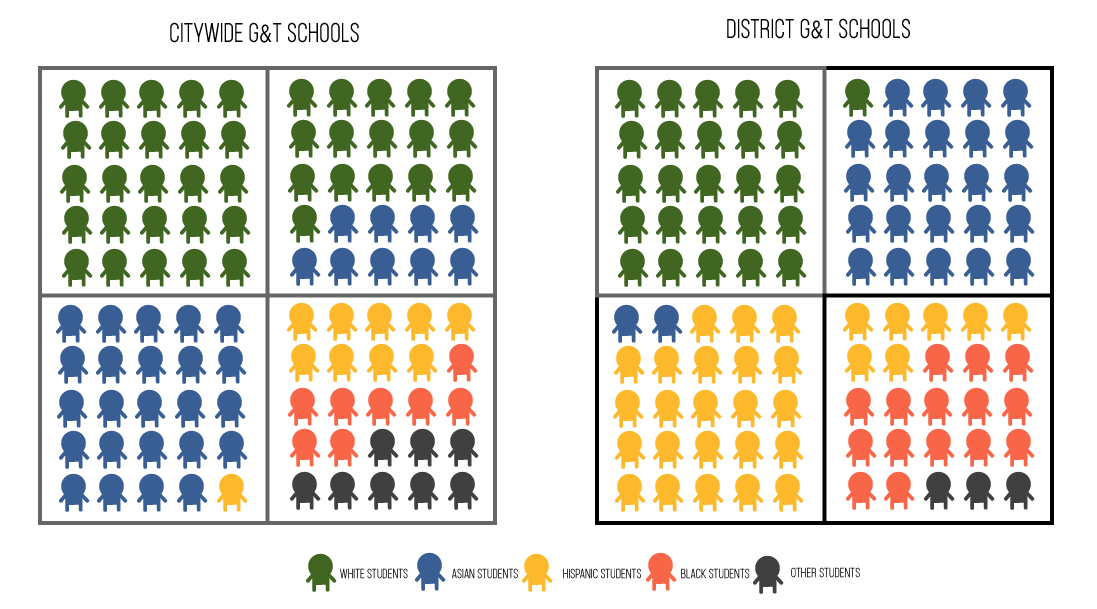

The graph shows the demographic breakdown of programs based on the grades schools serve. From the left, the K-5 and K-8 traditional public schools (TPS) can be considered the baseline for how schools look in New York City. The bars show the enrollment broken down by race, on average, across all K-5 and then K-8 schools in the city that do not have G&T programs. There is much higher enrollment in these two groups, but they show us a more general idea of what the city school system looks like. As we can see here, black and Hispanic students are comprising about 69% of student enrollment on average in K-5 schools, and 71% of K-8 schools, while white and Asian students are only 28% (K-5) and 27%(K-8) of the population in traditional public schools. Yet as we move across the graph to the center two bars, which are our K-5 and K-8 District G&T schools, we see a huge jump in the average enrollment for white and Asian students in these schools as compared to the traditional public schools, from 28% to 52% in K-5, and from 27% to 53% in K-8 schools. The black/Hispanic enrollment decreases from 69% in K-5 TPS and 71% in K-8 TPS to 45% in K-5 and 44% K-8 G&T schools. Finally, the rightmost bar shows us the enrollment broken down by race, on average, for the five citywide schools. These schools are not broken down by grade levels because they are such a small group with so few students, but they encompass the same idea: all of these children scored in the 99th percentile on the G&T admissions exam. This bar compared to the TPS bars shows the true racial disparity between schools without G&T and schools that are only G&T: the citywide G&T schools are not only majority white and Asian, but they admit so few black and Hispanic children in a city where they are the majority of the public school system. There is an average 18% enrollment of black and hispanic students in the citywide G&T schools as compared to 69% enrollment in K-5 traditional public schools.

In traditional public schools serving grades K-5, black and Hispanic students make up 69% of the students enrolled on average, whereas in the Citywide G&T schools, white and Asian students make up 74% of the students enrolled.

One of these things is not like the other

Looking more closely at the citywide G&T schools, there is an argument to be made that perhaps they have higher enrollment of white and Asian students because they are located in districts with that demographic makeup. The schools may be open to children from all over the city, but perhaps their student bodies look more like the neighborhoods they are in. After all, although school choice has been exercised more and more at the elementary school level, where only 60% of kindergarteners in the 2016-17 school year went to their zoned schools, black students are more likely to exercise school choice than white students.(Paradox of Choice) Residential segregation is still a reality, so comparing the citywide G&T schools to the G&T district schools and traditional public schools in their districts may be a more fair analysis of enrollment demographics.

While that is a logical explanation, the data tells a different story. The graph shows the demographic breakdown for the five citywide G&T schools, the traditional public schools in districts where they are located and the district G&T schools in the same districts. The traditional public schools are again our base demographics for what would be most representative of the neighborhoods in the area.

In District 1 on the Lower East Side, traditional public schools are 53% hispanic and 15% black on average, and the district G&T schools are about 51% hispanic and 19% black on average. NEST+m, the citywide G&T school in district 1, however, is only 12% hispanic and 8% black. On average, district 1 schools are only 16% white, but NEST+m is 40% white.

In District 3 on the Upper West Side, traditional public schools are 30% white on average, but the district G&T schools are about 35% white, and the Anderson School, the citywide G&T school in the district is 51% white. Asian students in the district make up only 5% of the students in traditional public schools on average, but in district G&T schools they are 8% of students. At the Anderson School that jumps to 27% of the student body.

In District 4 in Harlem, hispanic students make up 63% of enrollment in traditional public schools, on average, but at the district G&T schools they are only 54% of students on average. At TAG School for Young Scholars, only 17% of the student body is hispanic.

In District 20 in Brooklyn, white students make up 25% of traditional public schools on average, but 29% of the district G&T schools, and an overwhelming 67% of the student body at Brooklyn School of Inquiry, the citywide G&T school in the district. Asian students make up 46% of the traditional public schools, but only 41% of the district G&T schools and only 20% of the students at Brooklyn School of Inquiry, a trade off for the increased enrollment of white students.

Lastly, in District 30 in Queens, hispanic students make up 58% of the students in the district on average, but are only 35% of the district G&T schools. At the 30th Avenue School, the citywide G&T school in the district, hispanic students are only 9% of the student body. District G&T schools, 34% in District 30 actually have a larger average enrollment of white students than The 30th Avenue School, which is 31% white.

In general, while the districts where citywide G&T schools are located vary in their demographic makeup, they have fewer white students in traditional public schools than in the citywide G&T schools. Even in District 20, where on average Asian students are 46% of the students in the traditional public schools, the graph shows how they make up fewer seats at the district G&T schools and then at the Brooklyn School of Inquiry, while the average enrollment of white students grows. The citywide G&T schools and the district G&T schools are not only failing to be representative of the racial makeup of the public school system, they are not even representative of their districts.

Field Notes: Shock to the System

It was snack time at the citywide G&T school I visited, and we had just seen the middle school. Middle schoolers were a diverse bunch, learning skills for high school and very well behaved. As our tour turned the corner to the Kindergarten hallway, I cannot recall a time I have ever been so shocked at a school. Not a single brown or black face among the students giggling and eating snack on the floor. The middle school grades have some room for new students, so the student body upstairs was a solid mix of students. The elementary school grades are all G&T, and almost every student we walked by was white, with a few Asian students in each class. You could count the brown faces on one hand and still have fingers left over. It is a strange experience, to see a thing you have heard of, seen in data, but couldn’t imagine yourself. The school rarely has room in the elementary grades for students who test for G&T in grades above Kindergarten, so these students will stay together through elementary school.

Ability & Income:

Another way to look at differences between schools and programs is to look at students from special populations. The section looks at the differences in income, or whether a student comes from poverty, in TPS and the G&T program. This is followed by a discussion of students from two established special populations: students with disabilities, and English Language Learners.

Follow the Money

The G&T schools, both district and citywide, also look very different from traditional public schools when it comes to income. The majority of students in New York City public schools come from low-income families. In a city where the number of students in temporary housing has been steadily increasing to over 10%* (cite NYT), it is important that students are provided the services they need to succeed in school, which for poor students often means free meals, after school programs and counseling.

The other crucial thing to remember about special populations like low-income students, is that they generally come from families where parents are coping with difficult circumstances. In extreme cases, like students in temporary housing, parents may be moving their family from shelter to shelter, dealing with homeless services, and trying to find ways to provide for their children. Low-income parents who work multiple jobs, who are dealing with social services, or are unemployed are unlikely to have the same amount of time, let alone the money, to devote to visiting schools, filling out more than one application, or showing up to multiple appointments. Even if they do have children in a gifted program, low-income parents do not often have the time to visit or volunteer in schools, or to donate to parent teacher associations (PTA) or pay for any supplementary programming like after-school clubs or activities that may not factor into a school budget.

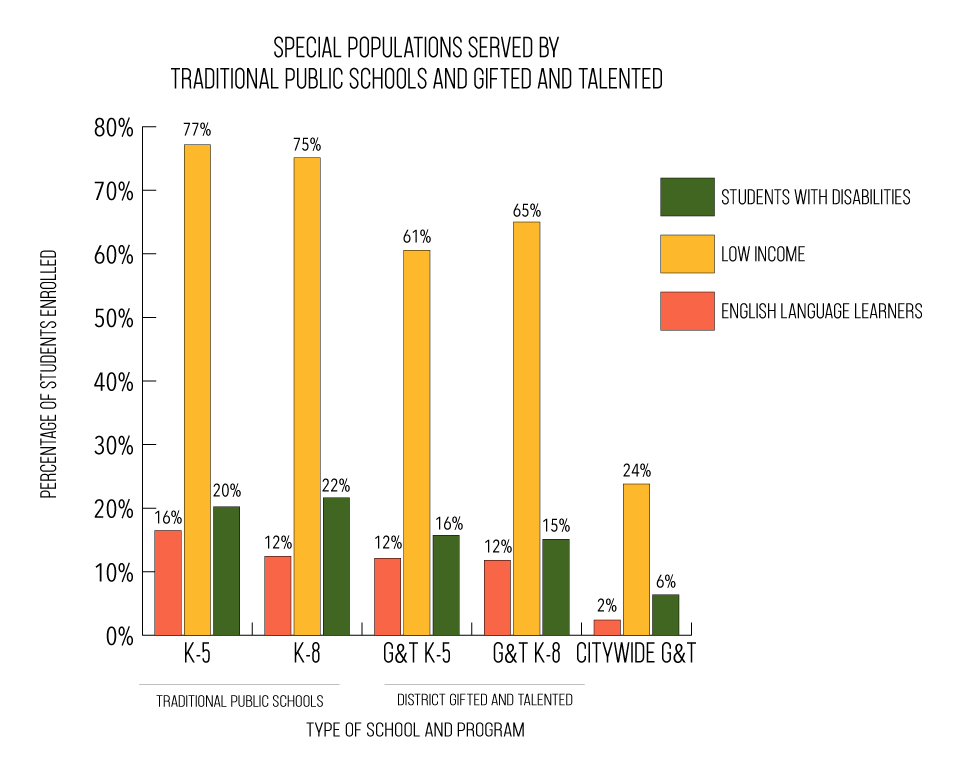

Low-income students make up 77% of the student population in traditional public schools serving K-5, on average. As the graph moves across to District G&T schools, only 61% of the students in K-5 are low-income. In a huge contrast from both TPS and District G&T, only 24% of the students enrolled at the five citywide G&T schools are considered low income. Student family income matters in determining additional funding for schools, like Title I funding, which is distributed by the federal government to schools with over 40% low income students.

Field Notes: The PTA

I tried very hard to concentrate on other areas of the citywide G&T school, besides it being a lily-white corner of New York City they had created in a public school surrounded by public housing complexes. The principal explained that each elementary class had a teaching assistant, as well as the lead teacher. One of the other visitors asked how the school could afford such an expense: having a second adult in every class could not be cheap for a public school that doesn’t receive additional funding for such things. The principal introduced us to a woman handing out juice boxes to some Kindergarteners, one of the PTA board members, and thanked her for their generosity which pays for everything from trips and clubs to teaching assistants. When asked how much the PTA generates per year, everyone was instantly uncomfortable and we were never given a straight answer, but told that it was public record. Over a million dollars last school year, was the magic number no one wanted to say out loud on the tour but that was reported to the IRS. The PTA website encourages each family to donate at least $1,200 per year to subsidize all the incredible programming the school offers.

Other Special Populations

The DOE makes an effort to provide students in special populations with the services and attention they need to learn. Students with disabilities(SWD) and English Language Learners (ELL) are the two major groups of students that receive specialized classrooms and curriculum, and are supposed to receive some kind of special service in every single public school in the city. G&T schools, both District and Citywide, do not exclude SWDs or ELL from applying, quite the contrary there are special testing accommodations for SWDs and the test is offered in different languages. Nevertheless, there is again a huge difference between the enrollment of ELL and SWDs at TPS in K-5 and K-8 and the G&T schools. Specifically, while SWDs and ELL make up 20% and 16% of the K-5 traditional public schools, respectively, only 2% of students in the citywide G&T schools are English Language Learners, and only 6% are students with disabilities.

The problem here is that there is a range of students with disabilities, and a child with mild autism may be better equipped to handle a G&T classroom than a student with a severe intellectual deficit, so there are different kinds of students attending a G&T school than a traditional public school. Their parents may also want them to attend a school with other children with disabilities, like a District 75 school which are made specifically to serve SWDs. Parents are also potentially dealing with medicaid, doctors, psychologists and therapists if their child has a disability, and may not have the time to deal with the effort to apply to a G&T school. Lastly, a long commute for a student with a disability may be out of the question to get to one of the G&T schools.

English Language Learners come from families where English is generally not the primary language, or is not spoken. Students may be wholly unfamiliar with the concepts on the G&T test, particularly children born outside of the U.S. Families that have recently emigrated to the U.S. are also dealing with a slew of other obstacles, including citizenship, employment, and social services. If figuring out how to sign a child up for Kindergarten is a challenge for immigrant parents who do not speak the language, they may not be up for additional steps and testing. There is also the fact that there are dual-language programs offered to ELL that are great quality and provide a great education in both English and their native language, while integrating them with children who are native English speakers and interested in learning a foreign language. This may be a much better fit for many ELL than the G&T program.

Field Notes: Familias Felices

I visited a traditional public school that lost its gifted program almost 10 years ago, in a primarily black and Hispanic district. The building was bright and cheerful, and there were pictures of happy children doing projects, at events, and with their parents all around the building. I saw a few parents around as we toured the halls, talking to teachers and visiting classes. In the main office, an administrator was explaining something to a mother in Spanish. The security officer in the lobby had a huge collage of pictures of past and present students, family holiday cards, letters and postcards on the wall behind her desk. She, too, was laughing with a family, in Creole, as she signed them in. The administrators who were giving me a tour steered me away from the desk to show me a mural the students had painted in honor of the new magnet theme of the school: multimedia studies. They were hoping the magnet title would attract new families to the school, because their enrollment had been falling for years.

Performance

There is also a discrepancy in the academic performance of schools with gifted programs and traditional public schools. This may not seem very surprising, but the degree to which high performing students are segregated into gifted schools may be. The discrepancies in performance also follow students to middle school and beyond.

Testing, Testing 1-2-3

The way that G&T schools outperform traditional public schools on state standardized testing is phenomenal and another indicator of the huge disparities between the program and the rest of the city. Statewide standardized tests in English Language Arts and math are still the primary methods for comparing performance at the school level and used in school accountability for how well children are doing in school, particularly in elementary and middle school. Students take state tests in the third grade through the eighth grade, and the test can change from year to year depending on what the New York State Education Department decides, but while it may not be super helpful to look at performance over time, it is useful in a single year to compare how different kinds of students are performing.

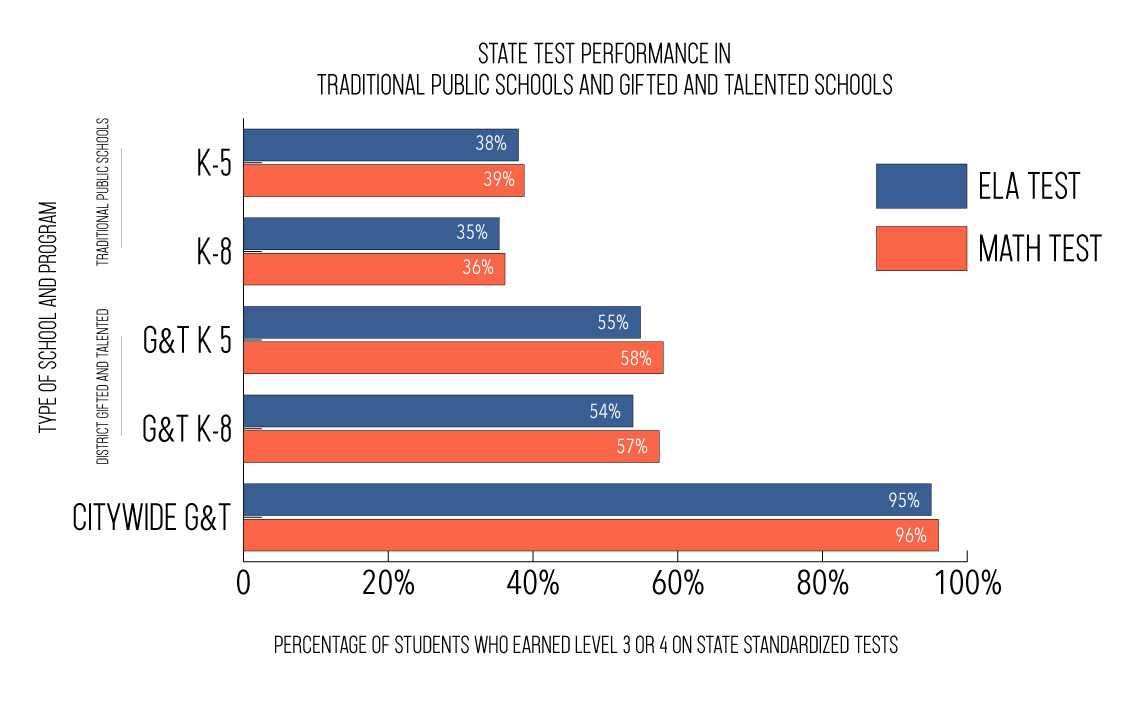

Students “pass” or are considered proficient in ELA or Math for their grade at a Level 3 or 4 result, (the test is graded on a Level 1 to 4 scale). An average of 38% and 39% of K-5 traditional public school students received a level 3 or 4 on the tests in ELA and Math, respectively, versus a whopping 95% and 96% of citywide G&T students in the last school year. This means that on average at a TPS elementary school, less than 40% of students are considered proficient for the grade level according to state standards, whereas close to all students in the citywide G&T schools are considered proficient.

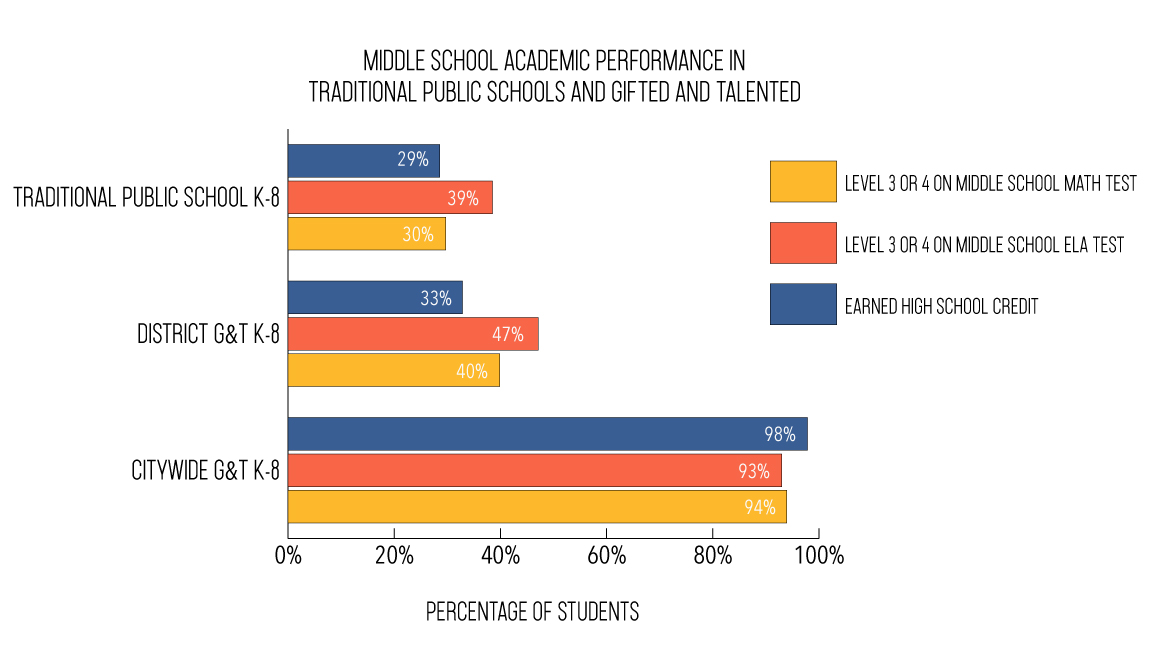

At the middle school level, students are also eligible to earn high school credit for taking ninth grade regents classes, like Living Environment or Algebra, in the eighth grade. While middle schoolers in NYC also take the state standardized tests in ELA and Math, programs are also evaluated based on how many of their students earn high school credit. This, of course, depends on whether the school even offers classes advanced enough for students to earn high school credit, but it is another factor in the difference between TPS and G&T schools.

There are no stand alone G&T middle schools, grades 6 to 8, because the program is only offered to the fifth grade, but there are many G&T schools that serve kindergarten to eighth grade students, and can be compared to TPS that serve K-8. Parents seek K-8 schools for many reasons, including avoiding the screening middle school process since fifth graders are guaranteed seats in the sixth grade if they choose to continue at the same school. District G&T schools that serve K-8 look a lot like TPS because they are admitting a whole new batch of students for middle school (and may have lost some of their G&T students to screened middle school programs). The three citywide G&T schools that offer K-8, however, with an astronomical 98% of students earning high school credit, compared to only 29% and 33% of students in the other programs, respectively, are outperforming both TPS and District G&T K-8 schools. The middle school students in the three citywide G&T K-8 schools are also outperforming other K-8 middle schoolers in both ELA and Math on the state tests.

Field Notes: The Green Screen

At the elementary school that lost its G&T program almost 10 years ago, the administrators were some of the most hopeful I’ve ever met. They had won a magnet grant after years of struggling with falling enrollment and terrible test scores, which meant they could afford all kinds of new equipment and technology for the school. I was shown a brand new Mac lab filled with computers, a “movement” room that looked like a physical therapist's office, and a green screen room where second graders learned to film PSAs on different natural disasters. My questions about testing and academic performance went unanswered, but I was shown the new smart boards in all the classrooms. The magnet grant was dedicated to the multimedia studies theme the school had adopted, so it was spent primarily on equipment and tech training for teachers. Most students in this school are not testing at proficient standards for their grade level in math or English language arts.

The differences between the gifted programs in New York City public schools and the traditional general education classes and schools is multifaceted and therefore it is important to look at the multiple ways in which the programs differ. It is easy to get hung up on one catchy statistic, particularly one about race, which is well documented and gets people interested in segregation. Segregation, however, as an idea and in reality, is measured by more than just racial differences, and can be based on income, different abilities, geography and performance.

Integration

Integration, or the diversification of student bodies in schools, has been identified as a potential solution to many of the academic performance issues in schools. It is also the proposed method of increasing equity in publics schools by advocacy groups, policy makers and educators. Integration has a plethora of benefits to students, both academically and cognitively, and has been identified as one of the ways to help to reduce racial achievement gaps. Students in more diverse schools perform better on tests, are more likely to go to college, less likely to drop out. These benefits extend to middle-class white students when they attend diverse schools, shown to promote creativity, motivation, critical-thinking, cultural sensitivity and problem solving skills. All students benefit from the challenge of learning to be around different kinds of people earlier on-- a fact of life they will confront in college, work and beyond. (The Century Foundation, 2016)

On average, students in socioeconomically and racially diverse schools—regardless of a student’s own economic status—have stronger academic outcomes than students in schools with concentrated poverty. -The Century Foundation

Advocacy

Integration has long been the goal of education advocates in New York City and cities across the United States. In the 1950s, Brown versus Board of Education set the legal standard to desegregate public schools, but the reality has been very slow, and often not realized in many counties and districts. Desegregation, as an educational reform strategy, was embraced in the 1960s and 70s when schools were federally mandated to desegregate, and busing and forced integration happened in districts across the country in response. These reforms failed to give parents a voice, and because of residential segregation children were sometimes traveling incredibly far to go to school under desegregation. Parents protested the policies across the country and in New York City white flight contributed to the decline of white and affluent students in the public school system.

Today, New York City has the largest public school system in the country, but it is one of the most segregated even in a city with residents from all over the world. The children in public schools are primarily black and Hispanic (close to 70%), but in school year 2016-17, half of the schools in the system had student bodies that were over 90% black and Hispanic. (Mader, 2017). Conversely, white and Asian students are segregated in schools where black and Hispanic students make up less than 50% of the student body. The DOE considers schools “racially representative” if the student body is between 50-90% black and Hispanic, which is an incredibly wide range, but only 502 schools in SY 2016-17 met that threshold.

Integration advocates have found that the city’s initiatives to diversify the school system are lackluster when it comes to racially integrating schools, primarily because gentrification and other urban phenomena are contributing to a rise in the number of white and affluent students and a decline in poor black and Hispanic students. With the change in proportions, saying that a school is “racially representative” when 90% of the student body is black or Hispanic is wholly inadequate. Advocates are protesting “screening” in all grade levels, an admissions method in which students must meet certain criteria for admissions based on GPA and test scores, sometimes including special additional testing, interviews and writing samples, because students of color and from low income households are often ill-equipped to meet the criteria. Some advocates have included the gifted and talented program in this protest: they want the city to eliminate the program entirely.

Eliminating Gifted and Talented

Without a doubt, the gifted and talented program as it stands is incredibly flawed. As an entry point to Kindergarten, it deeply segregates the school system due to its admissions process. Although the testing was championed as the most equitable way to identify gifted students when the program’s admissions were standardized, in over a decade of practice it has proven otherwise. Parents with the means to test prep their four year olds have found a way to funnel their children into select schools, self-segregating into a system meant to serve a special population of students: gifted children. The G&T citywide schools are not racially or socioeconomically representative of students citywide, and they do not serve their fair share of ELLs and SWDs as a result of the reality of the admissions process. Some research has even shown that black and hispanic parents do not consider the program a viable option for their children, because they would be an extreme minority in their classrooms. (Roda)

Nevertheless, even the education model that integration advocates are championing,the Schoolwide Enrichment Model (SEM), acknowledges that there are gifted children, and that they need differentiated learning, like all children of different abilities:

The Schoolwide Enrichment Model applies the know-how of gifted education to a systematic plan for total school improvement. Based on the belief that “a rising tide lifts all ships,” our goal is to increase challenge levels for all students and to promote an atmosphere of excellence and creativity in which the work of our highest performing students is appreciated and valued. This plan is not intended to replace existing services to students who are identified as gifted according to various state or local criteria. Rather, the model should be viewed as an umbrella under which many different types of enrichment and acceleration services are made available to targeted groups of students, as well as various subgroups of students within a given school or grade level. The centerpiece of the model is the development of differentiated learning experiences that take into consideration each student’s abilities, interests, learning styles, and preferred styles of expression. -School Enrichment Model

Gifted and Talented as it exists may not be fair or equitable, or even fulfilling its purpose of educating gifted children. Elimination of the program that isn’t careful to consider the needs of gifted students would be eliminating essential services and supports that could be carried over to a reformed program that is more adept at identifying gifted children. It is important to acknowledge the needs of gifted children before major policy change occurs.

Giftedness & Need

While pedagogy and identification methods for gifted children may be up for debate, the fact remains that gifted children need specialized and differentiated services in order to succeed in schools. Gifted children have been studied and considered a special population in schools for over a century. Educators, psychologists and researchers have been concerned with how best to educate and identify gifted children because at minimum they are in need of specialized curriculum in schools.

IQ Testing to National Imperative

Much of what has been studied about how gifted children are different from other children actually began with IQ testing in the early 1900s meant to study children with intellectual deficits and learning disabilities to separate them into special classrooms. Researchers realized these tests could be used to identify children of extraordinary learning abilities, and the gifted movement was born. Schools and studies began to put some of their theories into practice, opening gifted schools and programs and using testing methods to identify students as gifted.

1901

The first special school for gifted children in the United States opens in Worcester, Massachussetts.

1905

French researchers, Binet and Simon, develop a series of tests, called Binet-Simon, to identify children of "inferior intelligence" for the in order to place them in special classrooms separate from normally functioning children, (Special Education). Their theories of mental age revolutionizes the science of psychological testing by capturing intelligence in a single numerical outcome. (IQ testing)

1916

Lewis Terman, the “father” of the gifted education movement, publishes the Stanford-Binet, his expansion on the Binet-Simon, and based off of his extensive studies of gifted children and IQ.

1918

The Public Education Association of the City of New York assigned a psychologist to study gifted children at Public School 64.

1921

Lewis Terman at Stanford University examines the development and characteristics of gifted children into adulthood. His work, The Genetic Studies of Genius, is known today as the Terman Study of the Gifted, and is the oldest and longest-running longitudinal study in the field of psychology with a sample of 1,500 gifted children.

1923

Leta Hollingworth publishes Gifted Children: Their Nature and Nurture, which is considered to be the first textbook on gifted education. Her work dispelled many myths about gifted children and identified two major factors that caused adjustment issues seen in gifted children: untrained adults and lack of intellectual challenge.

1935

Leta Hollingworth founds P.S. 500 The Speyer School in New York City as a laboratory for studying gifted children through Teacher's College. It was the first example of a gifted elementary school in the city and featured differentiated curriculum carefully developed into units of study, the use of special enrichment options like foreign language and philosophy introduced at primary level to gifted children, and the use of diagnostic assessment for curriculum decisions in a nongraded setting

1957

The Soviet Union launches Sputnik, sparking the United States to reexamine the quality of American schooling particularly in mathematics and science. As a result, substantial amounts of money pour into identifying the brightest and talented students who would best profit from advanced math, science, and technology programming.

1958

The National Defense Education Act passes. This is the first large-scale effort in gifted education by the federal government.

1972

The Marland Report is published by the federal government, and the first formal definition is issued encouraging schools to define giftedness broadly, along with academic and intellectual talent the definition includes leadership ability, visual and performing arts, creative or productive thinking, and psychomotor ability.

1974

The Office of the Gifted and Talented housed within the U.S. Office of Education is given official status.

1983

A Nation at Risk reports scores of America’s brightest students and their failure to compete with international counterparts. The report includes policies and practices in gifted education, raising academic standards, and promoting appropriate curriculum for gifted learners.

1988

Congress passes the Jacob Javits Gifted and Talented Students Education Act as part of the Reauthorization of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act.

1993

National Excellence : The Case for Developing America's Talent, issued by the U.S. Department of Education, outlines how America neglects its most talented youth. The report also makes a number of recommendations influencing the last decade of research in the field of gifted education.

2002

The No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB) is passed as the reauthorization of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act. The Javits program is included in NCLB, and expanded to offer competitive statewide grants. The definition of gifted and talented students is updated again.

2002

The New York State legislature grants full control over the New York City public school system to the Mayor of New York City, Michael Bloomberg, beginning the era of mayoral control through the Department of Education.

2004

A Nation Deceived: How Schools Hold Back America’s Brightest Students, a national research-based report describes the ways in which American gifted children were in need of accelerated programming, which was not being employed by school districts in a substantial way to meet student needs.

2006

Joel Klein, Schools Chancellor of the New York City Public School system releases a memo announcing the standardization of gifted and talented admissions in public schools, eliminating the district run gifted and talented programs and introducing the one-test admissions system we have today.

The History of Urban Gifted Education, VanTassel-Baska, 2010 and A Brief History of Gifted and Talented Education, The National Association for Gifted Children

If the early 1900s were spent studying and establishing the existence of gifted children, the 1950s and the Cold War were spent trying to harness the abilities of gifted children. The United States government found that the education of gifted children, particularly in the fields of math and science, was a national imperative. In this era, legislation was passed at the federal level to providing funding for the education of gifted children. In the 1970s, the Marland Report provided the first formal definition of giftedness. This encouraged schools to define giftedness broadly, not only based on academic and intellectual talent. The definition included leadership ability, visual and performing arts, creative or productive thinking, and psychomotor ability. The definition has since been edited to exclude psychomotor ability, but it has been used in policies, studies and reports ever since. The report also explicitly stated that gifted children should be identified by “qualified persons” and required “differentiated educational programs” than those provided by schools:

Gifted and talented children are those identified by professionally qualified persons who by virtue of outstanding abilities are capable of high performance. These are children who require differentiated educational programs and/or services beyond those normally provided by the regular school program in order to realize their contribution to self and society. Children and youth with outstanding talent perform or show the potential for performing at remarkably high levels of accomplishment when compared with others of their age, experience or environment. (U.S. Department of Education, 1972, 2)

The end of the 20th century saw many studies and reports evaluating the work that had been done to provide services for gifted students in public schools post-Marland report. In 1993, National Excellence : The Case for Developing America's Talent, a report issued by the U.S. Department of Education, explained how the country had neglected its most talented youth and made a number of recommendations which influenced research in the field of gifted education for the rest of the decade. The report also notably argued that gifted students were not restricted to a particular race or socioeconomic class: “Outstanding talents are present in children and youth from all cultural groups, across all economic strata, and in all areas of endeavor.” (U.S. Department of Education, 1993, p. 3) In 2002, under President George W. Bush, the No Child Left Behind Act, (NCLB) modified the definition of gifted and talented students again:

Students, children, or youth who give evidence of high achievement capability in areas such as intellectual, creative, artistic, or leadership capacity, or in specific academic fields, and who need services and activities not ordinarily provided by the school in order to fully develop those capabilities. (No Child Left Behind Act, 2002)

Again, this modern definition established that gifted children need services that a school or general education classroom may not ordinarily provide.

So, how did we get here?

Public schools went under mayoral control in New York City in 2002. Public schools had been run by smaller local districts and regions under the Board of Education (Board of Ed), which was comprised of members appointed by the borough presidents. With the introduction of mayoral control under former Mayor Michael Bloomberg, he appointed a school’s chancellor to oversee the Board of Ed, and increased the size of the board to have a majority of members he appointed directly. In 2006, the schools chancellor Joel Klein announced the centralization of the gifted and talented programs under the DOE. The DOE would set standardized admissions to the programs under a single admissions process that uses the Naglieri Nonverbal Ability Test and the Otis-Lennon School Ability Test, administered at once. The thought was that because G&T seats in districts went to primarily white students, and that studies in other states had found bias in teacher recommendations to gifted programs, a standardized admissions test would eliminate that bias and diversify the program. In the first few years of the program, the NYT found that the program was actually admitting fewer black students and more white students than it previously had, and it actually struggled to garner much popularity, closing several programs for lack of demand.

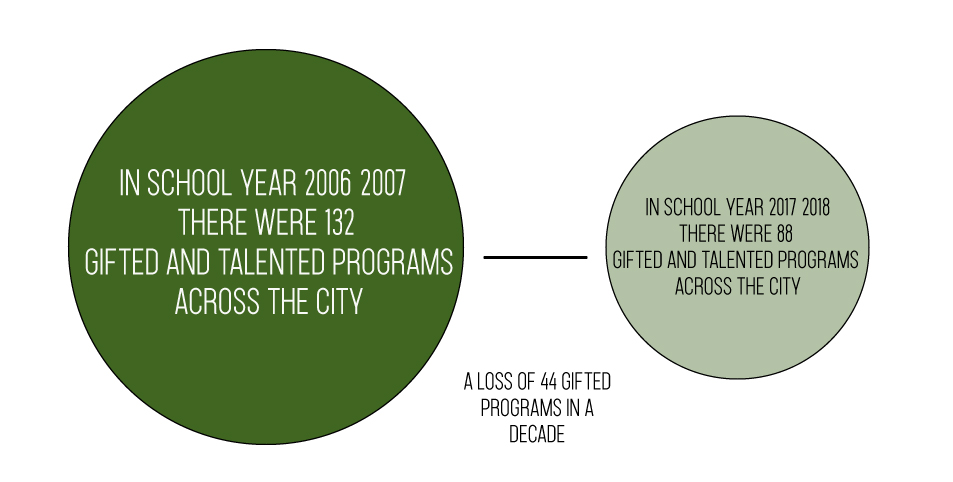

Gifted and talented programs in New York City have always been favored by white middle class residents as a way to access higher quality education for their children in the public school system. The DOE under Mayor Bloomberg was aware of this, and part of the standardization was to encourage these families to stay in the system which was majority hispanic and black. The story has not changed much, but under district and regional control there were substantially more G&T programs available across the city, not just in select districts. There were 132 gifted programs in the 2006-07 school year, the last year G&T was run by schools and districts, before centralized control. There are only 88 gifted programs in New York City today including the five citywide G&T schools.

Data Source: NYC Department of Education

This means that the city lost 44 gifted programs in just a decade of mayoral control over the program. While the DOE defends this decline, which has fluctuated over the years (there were 135 programs in the 2009-2010 school year, up from 112 in 2008-2009), they claim to have shuttered programs where “demand” for the program was low.

Using demand as rationale for hosting gifted programs in some districts and not in others is exactly the kind of thinking that leaves gifted students underserved. The argument that desire is what dictates funding and implementation of a program over the needs of gifted children who are likely going unidentified is troubling to say the least, and is a wholly inappropriate view of gifted education. Using a public school program meant to serve a special group of children as a way to keep certain populations in the public school system is a repulsive use of policy to favor some families over others in the name of differentiated services and integration efforts. Gifted children do not come from one specific neighborhood, they are not of a specific race or background, and giftedness is not born from a parent’s wealth: giftedness, like a disability, is trait that defines the special needs of a student.

Reframing Giftedness

Gifted students in New York City, however, are often not considered a group in need. They are not classified as a special population in the same way students with disabilities, students in temporary housing and English Language Learners are. The difference between these established special populations and gifted students is that special populations are seen as students lacking the ability to learn without additional aid and resources, and gifted students are seen as highly able to achieve academically. In reality, like other special populations, gifted students need specialized services and additional resources to learn because their academic potential is measured above grade or age level.

Giftedness is multifaceted, encompassing more than just intelligence identified by a test score. Theorists like Joseph Renzulli defined three components of giftedness: above-average intelligence, task commitment and creativity. (Renzulli 1978) Renzulli also discussed later findings by Lewis Terman, the “father” of gifted education, that indicate that even Terman eventually came to conclusion that IQ was not the only determinant of “giftedness”, but rather that there is something about motivation, confidence, and traits that could not be ascertained by a test, that make someone gifted.

In the 1920s, Terman began the Genetics of Genius study, a long-term study of gifted children that followed the them through adulthood, and continues today as the Terman Study of the Gifted. Terman identified 1,444 children with extremely high IQ by using his Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scales, and although his study was incredibly tainted and ungeneralizable to the greater population (his subjects were all from California, born between 1920-1925 and almost all white from middle and upper-class families), he did eventually find that what made some of his children successful in adulthood was a differentiation in “personality factors” since they all measured the same on IQ tests:

A detailed analysis was made of the 150 most successful and 150 least successful men among the gifted subjects in an attempt to identify some of the nonintellectual factors that affect life success... Since the less successful subjects do not differ to any extent in intelligence as measured by tests, it is clear that notable achievement calls for more than a high order of intelligence. The results indicate that personality factors are extremely important determiners of achievement...The four traits on which differed most widely were persistence in the accomplishment of ends, integration toward goals, self-confidence, and freedom from inferiority feelings. In the total picture the greatest contrast between the two groups was in all-round emotional and social adjustment and in drive to achieve. (Terman 1959, 148)

Renzulli and Terman give us an understanding of how complex defining giftedness can be. They were also both proponents of using those definitions for the purpose of bettering the education of gifted students via the use of specialized resources:

Gifted and talented children are those possessing or capable of developing this composite set of traits [above-average intelligence, task commitment and creativity] and applying them to any potentially valuable area of human performance. Children who manifest or are capable of developing an interaction among the three clusters require a wide variety of educational opportunities and services that are not ordinarily provided through regular instructional programs. (Renzulli 1978).

Assumptions about gifted students and their ability to “make it on their own” when left to their own devices in the classroom are myths. Research into the development of gifted children has shown that gifted children face their own developmental problems in light of their above-average intelligence, like social isolation, heightened sensitivity and frustration when they are not provided with appropriate attention and services in schools.(Callahan Child Dev II) Gifted children are often misunderstood by untrained adults, and many of the same characteristics that are positive identifiers can be misinterpreted as negative or inappropriate behaviors when gifted children are compared to children their age. For example, gifted children can develop high sensitivity to the expectations of others at very early ages, and instead of being encouraged to nurture those feelings in a healthy way, adults can interpret them as overly vulnerable to criticism and needy for recognition. (438) Gifted children can develop a sense of justice and fairness earlier than other children, and that may been interpreted as idealism, leading to frustration on the child’s part when they are not taken seriously. In the classroom, gifted children can connect ideas and see complex relationships between concepts that others will not understand yet, and that can be seen as “off topic” and disruptive to the lesson. Gifted children, therefore, not only require specialized curriculum to learn closer to their potential, but also teachers and administrators who can understand their unique developmental needs. (Callahan 1997, 431-440)

What this research shows is that not only is identifying gifted children complex, but that they undoubtedly need special services in schools. Renzulli and Terman and countless other psychologists and theorists have shown that in all the complexity of defining giftedness, using only a single method is an inappropriate way to identify gifted children. IQ testing may be used in conjunction with a multitude of other methods, but should not be relied on as the sole indicator of a child’s potential giftedness. Callahan adds a deeper understanding that while yes, gifted children need advanced and accelerated curriculum due to their abilities, they also need additional services not normally provided in a general education classroom because they develop characteristics and behaviors that may be misinterpreted by untrained educators. Add to this the government definitions of giftedness discussed earlier that explicitly state a need for differentiated services, and we are poised to take a new look at gifted education public schools.

When we define special populations as “need based” or “resource based”, instead of based on ability or lack thereof, we no longer consider the label “gifted” a commodity or privilege. Our debate can focus on whether we are adequately serving this group of students and less on the competition to be identified in the group. Reframing the definition of giftedness based on the needs of gifted students will allow us to tackle troublesome policies that create unfairness and inequality in education, for all our students.

Conclusion

Why does this all matter?

No one questions whether students with disabilities (SWDs) deserve to have separate and specialized programming, and rarely do people question if the students we identify as SWDs fall within that category. In fact, some parents would prefer their children not be labeled by their abilities, and sometimes these students are identified but do not receive adequate resources. Nevertheless, there is a systematic/standardized way of identifying those students, but it is more situational, as in parents, teachers or administrators initiate that identification on a case by case basis, there is no universal testing or societal encouragement for a student to be identified as an SWD. If we broadly define giftedness, whether that be on a basis of above average IQ, above grade level achievement, or above age psychological and emotional maturity, or a combination of factors, as well as take into consideration the additional needs of these students (specialized pedagogy, additional resources, specialized teachers), we would be able to craft a fairer process for identifying gifted students. Until we identify students in a manner that considers their “giftedness” a condition needing alternate or additional services, and not an elite label or reward, we won’t be able to assess the G&T program flaws, like the failure to standardize their curriculum, their access to resources, lack of funding, inequity in program locations, etc. We have to stop using G&T as a means to a “better” education, because we cannot say for sure that the gifted are actually being served in the current system.

Field Notes: The Library

The principal led us to a third grade classroom at the citywide G&T school. I loved the third grade, it was the first year I was in a gifted program, so I was excited to see the classroom. The teacher, a cheerful woman with over a decade’s experience teaching at the school, proudly showed off her bulletin board displays and different “learning areas” of the room for math, history and science. I followed along the edge of the room until I got to the in-class library. I asked why some of the books were in baskets with letters on them, what did the letters mean? The teacher explained that this was commonly done in classrooms now and books were separated by reading level, so A, B and C were very easy reading at about first grade level, and it went all the way up to V which was beyond fourth grade reading. I guess she noticed my confusion because she quickly added that some students weren’t always ready for third grade reading and some of her advanced students liked to go back to old favorites from time to time. As for the more advanced books, sometimes the content was difficult to understand, but she hoped most of her students would eventually get to some of those books. She beamed at her library and I smiled as she showed us her Junie B Jones basket, books I had loved reading in the first grade. Her students loved them, too.

Oh, okay. So what should we do?

The current G&T admissions process does not convincingly identify gifted students using methods that experts suggest. While most experts recommend some combination of academic achievement records, interviews and observations, portfolios, and teacher input, they do not believe that tests as the only indicator of giftedness is an effective identification method. Researchers also generally agree that accurate IQ determinations under six years old are difficult. Jonathan Plucker, a Johns Hopkins University professor of talent development, recommends universal screening for giftedness in third or fourth grade. “If you screen everybody, it’s amazing how much more diverse your student population gets.” (Wall Street Journal, 2018)

It is also problematic that we call it an admissions process, and that families have to express interest and fill out applications, because that is not the same as identifying a student as gifted, the admissions process just labels students who fulfill certain requirements as gifted. While the IQ testing method in place may capture some gifted children as experts would define, it is doubtful that it is capturing all or even a majority of children that would be considered gifted if they were tested later and held up to broader standards by psychological reviews, academic achievement portfolios and teacher recommendations later in life.

This is not a formal policy report and I will not pretend to be able to make a recommendation on such a complex issue which affects not only the children currently enrolled in gifted programs, but the over a million children studying in the inequitable public school system in New York City. I do hope that a few big points can be taken away from this research and analysis of the issue:

- Policy, under the guise of doing something to promote equality, cannot deliver on its promises if it comes from unfair or unjust premises and pretenses.

- Gifted children come from everywhere and anywhere. They are not defined by the color of their skin or their parents’ abilities to provide for them. It is in the public’s best interest to find them and nurture them, like other children in need, no matter where they come from.

- Integration in public education is not just about lifting children of color or low-income families. It is about creating a more fair, understanding and thoughtful society, and benefits us all.

Thank you!